The first line of the Crown Forest Sustainability Act sets the direction: “…to manage Crown forests to meet social, economic and environmental needs of present and future generations.” Listen to the story learn about how the act got put into place.

The Crown Forest Sustainability Act (CFSA), passed in 1994, brought new thinking to the way Ontario’s forests are managed.

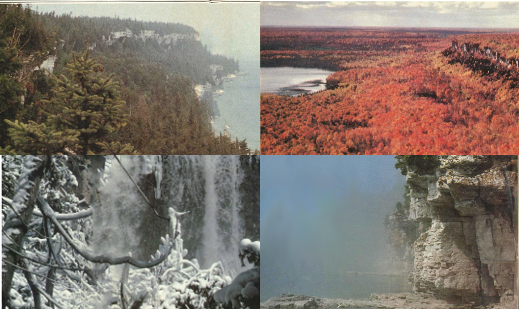

Up to the 1990s, Ontario’s Crown forests (forests on publicly owned land) were thought of mostly as a commodity. Protecting the forests’ waters, air quality, wildlife, recreation and tourism use and aboriginal rights, while considered, took a back seat. It’s an important point, because Ontario has more than 71 million hectares of forest, and 90 per cent of this is Crown forest.

The CSFA put environmental considerations into forest management. It came into being after years of hard work. Much of it was done by C. J. (Bud) Wildman, the Minister of Natural Resources and Minister Responsible for Native Affairs from October 1990 to February 1993. He worked closely with Assistant Deputy Minister David Balsillie and Policy Advisor Marty Donkevoort.

Background

Between 1965 and 1994, the average yearly area logged in Ontario had gone up more than 50 per cent, to nearly 210,000 hectares. During that time period, the actual timber harvested on Crown land more than doubled from 10 million cubic metres of wood cut from an area of 1,000 hectares of forest, to nearly 21 million cubic metres from 2,100 hectares.

Worse, the use of clearcutting kept growing. In the 1970s, about 70 per cent of Ontario’s forest harvests were clearcut. By the 1990s this jumped to 91 per cent.

Clearly, this wasn’t sustainable. As unthinkable as it may seem, if soxmething didn't change, Ontario could eventually run out of harvestable, renewable forests. Previous ministers and governments had considered this problem with varying interest and attention, but the mind-set was to put the short term needs of forest companies for product — trees to be cut — before protection or renewal and long term interests.

Bud Wildman and the MNR reform

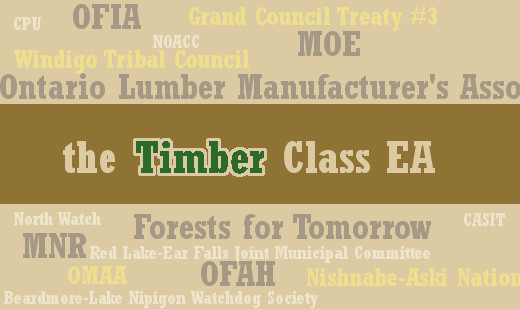

When Wildman took office as minister, Ontario’s forests were regulated by 28 forest management agreements, covering 70 per cent of Crown forests.

He represented the Northern Ontario riding of Algoma for the New Democratic Party (NDP), knew the forests and the forestry industry well. He was determined from the day of his appointment to bring change to the Natural Resources ministry and the way it managed forests, to make sustainability a priority that would have to be considered in every decision.

The concept of ‘sustainable development’ was recent; the phrase had been coined only in 1987, in a United Nations report called Our Common Future or the Brundtland Report, which firmly placed environmental issues on the world’s political agenda. It was important that everyone understood where Ontario was going, and that the industry understood that sustainability was ultimately better for its bottom line.

The MNR staff was highly professional and had some of the most experienced forestry experts in the world, but under the rules at the time, the forest industry (not the ministry) was responsible for making sure that forests were being regenerated. Since the Crown, not the industry, actually owned the forests, the industry’s priority was to get permission to harvest as many trees as possible. The mindset of the ministry staff, and virtually all ministers up to this time, was to follow the rules and make tree-cutting, not sustainability, the priority.

Wildman wanted to change this. There weren’t enough trees being regenerated. In many of the unregenerated forests, ‘weeds’ like birch and poplar trees were growing.

Altering the tree species affects the type of insects and plant life in the forests, as well as the soil, the water, and ultimately the fish and all other wildlife. This not only affects the forests, but also the biodiversity, fish and wildlife habitats, recreation, tourism, spiritual and heritage values of our forests. Wildman felt that Ontario had to move to a holistic approach to forest management, taking all of these values and interests into account.

He knew there were a lot of mid-level staff and field workers in his ministry who shared his concerns. They would support figuring out better ways to protect Ontario’s Crown forests.

He also knew he needed to act fast, because changing the MNR and its forestry practices would take a long time (it did take nearly the whole term of the NDP government) and there would likely be unforeseen obstacles.

The unforeseen obstacle came quickly when the NDP government, elected in September 1990, soon discovered it was broke. Wildman was told he wouldn’t have enough money for a major forestry audit— Ontario’s first. This was important because the Ministry assessments of the state of our forests were out-of-date. So despite the lack of cash, Wildman and his team found a way to do the audit anyway, through a comprehensive program, known as the Sustainable Forestry Initiative.

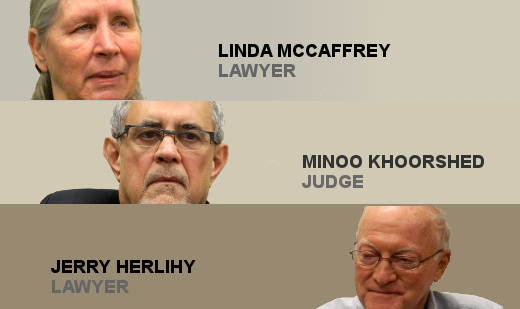

The Crown Forest Sustainability Act - Now

The Act was finally passed in 1994 (last updated in 2003). It sets detailed rules for how Crown forests are to be managed, in terms of access, maintenance, renewal and planning — rules that are binding on the MNR and everyone else. It incorporated the majority of the recommendations of the Class Environmental Assessment on Forest Management and covers the entire province but primarily affects the North, where most of Ontario’s Crown forest is located.

The result is a system that has everyone thinking more holistically about forests. The CFSA and the talks that preceded it also involved more detailed discussions with Ontario’s First Nations than had taken place in the past — a dialogue that is still evolving.

Today, thanks to the CFSA, there is a more clear, explicit idea of what is expected — the limits to harvesting Crown forests, when it’s appropriate to allow development and roads and when it’s not, and most importantly, the need to make sure that forests that are harvested are properly regenerated. Although disagreements still come up over issues (such as road building and development), the Act allows them to be considered during the planning stage, so they can be considered with sustainability in mind.

Thinking has changed across Canada about forestry. In 2010, nine environmental groups signed the historic Canadian Boreal Forest Agreement, aimed at working together. There are still ups and downs — environmentalists and loggers hit an impasse over this agreement in 2013. But Ontario’s Crown Forest Sustainability Act set the trend for the new way of looking at forests as a legacy worth sustaining.

Wildman and his colleagues worried that the Crown Forest Sustainability Act would not survive after the government changed hands. But it has changed hands several times and the law is still there. Ontario’s thinking about sustainability has changed too.