As designated environmental reporters in the 1970s and 80s, Howard, Israelson and Keating played a critical role in conveying information gathered from academics, scientists, governments and non-governmental organizations to the public.

The Journalists

Of all information sources, newspapers have traditionally been the most influential. Their high profile stories coming out early in the day are picked up by radio, television and now Internet news sites. Because of this, they often set the agenda for public and political debates. In the 1970s, rising public interest in environmental issues prompted editors at Canada’s major newspapers and later at some broadcast outlets to create an environmental “beat” on a par with health or education, and reporters were directed to track down and report on the most exciting and often alarming developments in this field.

At the Toronto Star where he worked from 1975 to 1984,

Ross Howard became one of Canada’s first environment reporters.. For Howard, it was an “amazing time” of transition when pollution was becoming a serious subject of scientific study and public concern rather than simply a series of unconnected stories about irritants like litter and trash, and he specialized in writing about environmental issues for eight years of his journalistic career. When Howard gave up his post in 1984,

David Israelson, who worked at the Star from 1983 to 1998, succeeded him, beginning in 1985. Similarly, the Globe and Mail, in response to the high level of public interest, had its own dedicated environmental reporter,

Michael Keating, an experienced journalist who covered these issues for the Globe from 1979 to 1988.

The Toronto Star and the Globe and Mail were then, and still are, among the most widely read newspapers in Canada. While the Globe sees itself as the authoritative voice of Canadian journalism with a national reach and a political-economic focus, the Star with the highest circulation of any paper in Canada, has long pursued a populist middle-class stance and more aggressive reporting towards selected issues.

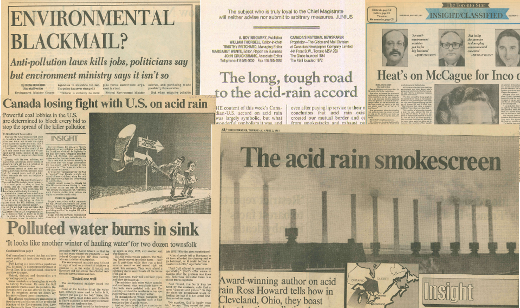

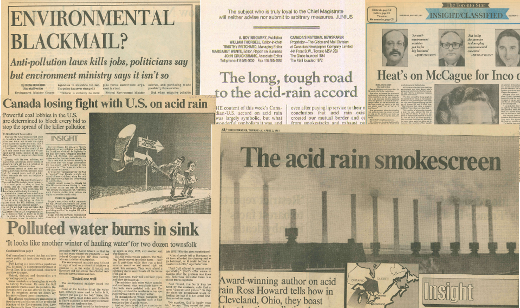

Breaking Environmental News

As designated environmental reporters in the 1970s and 80s, Howard, Israelson and Keating played a critical role in conveying information gathered from academics, scientists, governments and non-governmental organizations to the public. Reports, lawsuits, lobbying campaigns, commissions, government announcements, the results of scientific studies and leaked documents all provided breaking news, and the level of public interest was high.

In following professional standards of accuracy, fairness and balance, these reporters had to weigh claims and counter-claims made by emerging groups and individuals who wanted their environmental issues covered by the press. The journalists also had to try to assess the risks of pollution problems to public health and the environment, recognizing that in a time of heightened public interest and concern their reporting could influence significantly how issues were perceived and managed.

Although none of the three reporters in this session were trained as scientists, their on-the-job education gave them a rich understanding of the science behind environmental issues – the consequences of air and water pollution, the risks of chemicals to human health, or the effects of long-range transportation of acid-rain causing emissions on prized areas such as Muskoka Lakes. During the period when they were writing, many “brave” scientists, as Howard calls them, both inside and outside federal and provincial governments, took the time to explain the complex science behind these issues both on and off the record. This investment in educating reporters was reflected in the high level of sophistication found in news stories about acid rain, dioxin contamination of the Great Lakes and other headline environmental issues of the day.

The Political Hot Seat

Environmental news began to regularly command front page headlines and extensive explanatory stories. With the support of their editors, the three journalists kept environmental issues at the forefront of public awareness, which considerably influenced a sea change in public attitudes: where pollution had once been regarded as the cost of doing business and considered a fair trade-off for economic benefits, a better-informed public became attentive to exposures and risks and losses and consequences and began to demand greater corporate responsibility and government action.

The environment became a political hot potato. Almost daily the Ontario Minister of Environment had to be prepared to answer to the press, the public and the provincial Legislature every time a story broke, and the heat proved too warm for many of them. As Keating pointed out in one of his many front page stories, there was a turnover of five Environment Ministers in seven years in Ontario during the years of Progressive Conservative governments. The heat was almost unrelenting but its sources were as diverse as the global environment itself -- an explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear plant in the Ukraine, the chemical leak at Union Carbide in Bhopal, India, a radioactive spill from the Pickering nuclear plant, the discovery of dioxin in herring gull eggs taken from the Great Lakes or maple trees believed to be dying from acidified rain.

As the media continued to highlight these stories, the public mood gradually changed from concern to alarm. The Ontario government realized that the environment was more than an engineering problem and began to assert higher protective and preventative standards. Tougher legislation that required greater corporate accountability and costs was directed at specific environmental problems such as acid rain. Enforcement was strengthened to ensure that companies controlled their spills and emissions more effectively.

By putting environmental issues on the front page and making them a frequent subject for editorial comment, water-cooler conversation and protest, environmental journalists were instrumental in changing public perceptions of pollution by the early 1980s. These journalists kept the issues high in opinion polls, instigated wide-ranging policy debates and ensured a new degree of political accountability for the state of the environment.